Jaime Marco, Antonio Morant

Cognitive Impairment

Hearing loss or hearing impairment is a prevalent condition. It affects 360 million people around the world. It determines various levels of disability, ranging from the physical aspect to social and psychological aspects. The incidence and prevalence of hearing loss is expected to increase considerably over the next few years, due to the demographic transition experienced around the world1.

A hearing loss greater than 40 dB in the better hearing ear in adults, and greater than 30 dB in the better hearing ear in children is considered a disabling hearing loss. At present, 80% of the population with impaired hearing live in developing countries, low- and medium-income countries. Hearing loss is a true public health challenge, undoubtedly. It is the most frequent sensory deficit among humans1.

Approximately a third of people over age 65 have a disabling hearing loss2.

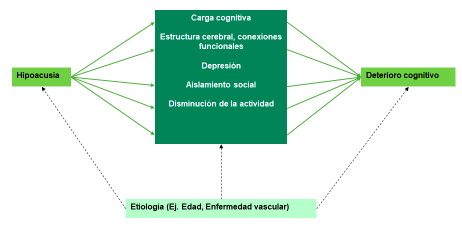

Three different theories accounting for the association between hearing loss and aging have been put forward in the scientific community:

The first theory, developed through neurophysiological studies and supported by neuroimaging, uses the cognitive overload concept in reference to the brain activity needed to understand and recognize a voice, even though neural plasticity can offset any decline in working memory, hearing and neuronal organization, even in adults.

The second theory is that social isolation and depression provoked by the hearing impairment create a negative perception of one’s own health and a reduction in daily activities.

The third theory is that the role of an aged central and peripheral nervous system can alter the synapsis and the anatomy of the central nervous system.

These three theories are not exclusive, but rather they overlap and have influence on the overall clinical status of an individual. All of this results in irreversible neural disorganization, which then triggers an impairment in one’s ability to understand the spoken language. Other issues, such as cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease and other comorbidities and lengthy hospital stays can precipitate this trend (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The effect of sensory impairment on the central nervous system and the diseases that affect it.

On average, individuals with hearing loss need 7.7 years to develop a cognitive impairment score of 5 in the 3MS test (a test well-established as indicator of the level of cognitive impairment), compared with the 10.9 years a normal-hearing person would take to score that3, 4.

Lin’s results4-5 are consistent with previous publications that show the association between a more severe hearing loss and a poorer cognitive function in verbal and non-verbal cognitive tests 6.

In theory, there are several mechanisms involved in the association between hearing loss and cognition. Poor verbal communication associated with hearing loss can lead to errors in cognitive tests. Besides, hearing loss may be overestimated in individuals with subclinical cognitive impairment. Communication difficulties rarely occur as a result of hearing loss (unless it is severe). They are an unlikely hindrance of face-to-face communications in quiet environments (that is to say, when cognitive tests are taken), particularly when experienced staff is doing the testing7. Lin considers their results to be consistent both in verbal tests (3MS) and non-verbal tests (DSS).

Pioneering studies by Lin4, 8 and Amieva9 suggest that the population of older adults with poorly treated hearing loss are more susceptible to different types of cognitive impairment. People with mild, moderate and severe hearing loss are respectively 2, 3 and 5 times more susceptible to dementia than a normal-hearing person. If so, memory loss and cognitive impairment could increase, as the brain must make an additional effort to interpret the sounds it has trouble to receive. Some proposals consider this association can vary when a hearing-impaired person is timely diagnosed and receives a suitable hearing aid9. However, Wong et al10 state that the use of hearing aids alone is not enough to curb cognitive decline in hearing impaired individuals.

People with hearing loss see their cognitive skills diminish 40% faster than normal-hearing people. Studies associate this reduced brain function with the hearing level directly (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The effect of hearing loss on speech perception, mental effort and cognitive impairment.

Several studies4, 9,11,12 declare that hearing loss is associated with poor cognitive execution, and therefore it contributes to the overall cognitive decline. The emotional state is limited due to social isolation and depression. One theory proposes that “if the brain allocates additional resources to try and listen to what is happening, it is probably taking those resources away from elsewhere in the brain, such as thinking and memory”. Another effect is that Brodmann areas 41 and 42, in charge of hearing, receive less auditory information. Some proposals consider this association can vary when a hearing-impaired person is timely diagnosed and receives a suitable hearing aid9, 13.

Addressing hearing loss with hearing aids can alleviate or improve cognitive function in these patients and favor their social engagement. However, they state that the use of hearing aids alone is not enough to curb cognitive decline in people with some sort of hearing loss 10. Since close to 10% of people over age 60 have hearing loss, and 7 years go by from the moment a patient starts having hearing problems to when they decide to use a hearing aid (based on some studies); the population of older people with cognitive impairment is going to be quite large, unless their hearing loss is addressed on time.

The research9 undertaken by the University of Bordeaux with more than 3,700 people indicated that people who address their hearing deficit with these devices rate better in psychological tests that assess their mood and cognitive skills. The results of the research indicated that individuals with more severe hearing impairments showed less cognitive skills and more symptoms of depression. Conversely, individuals who used their hearing aids had similar cognitive skills to those of normal-hearing individuals.

In short, we currently have sufficient information to confirm that any type of hearing loss—although sensorineural hearing loss is the most researched—is one of many factors having impact on the acceleration of cognitive impairment. We also know that hearing loss is the third most frequent disease in older age. The effect of palliative treatments, such as hearing aids, cochlear implants and mere sound amplifiers can reduce, slow and even stop cognitive impairment.

Let us not forget the economic impact of social aid and direct and indirect costs of treatment for people with cognitive impairment.

A study carried out in Australia totaled the cost for the total population at AUS$ 302,307,969 per year 14

All these bibliographical references must encourage us to carry out this type of study with Spanish speakers in Spain and Latin America.

References

- Constanza Díaz, Marcos Gooycolea, Felipe Cardemil. Hipoacusia: Transcendencia, incidencia y prevalencia.. Rev. Med. Clin. Condes 2016; 731-739.

- https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

- Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2127-213315888561

- Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology. 2011;25(6):763-77021728425

- Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214-22021320988

- Valentijn SA, van Boxtel MP, van Hooren SA, et al. Change in sensory functioning predicts change in cognitive functioning: results from a 6-year follow-up in the Maastricht Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):374-38015743277

- Gordon-Salant S. Hearing loss and aging: new research findings and clinical implications. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42(4):(suppl 2) 9-2416470462

- Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD; Kristine Yaffe, MD; Jin Xia, MS; et al. Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293-299. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868

- Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Giulioli C, Meillon C, Rullier L, Dartigues JF. Self-Reported Hearing Loss, Hearing Aids, and Cognitive Decline in Elderly Adults: A 25-Year Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Volume 63, Issue 10, October 2015, pp. 2099–2104.

- Wong LL, Yu JK, Chan SS, Tong MC. Screening of cognitive function and hearing impairment in older adults: a preliminary study. Biomed Res Int. 2014: 852-867. doi: 10.1155/2014/867852.

- Salthouse, TA y Meinz, EJ. Aging, inhibition, working memory, and speed. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995 Nov; 50 (6): 297-306.

- Petersen, R; Knopman, D; Boeve, B; Geda, Y; Ivnik, R; Smith, G; Roberts, R and Jack, C. Mild Cognitive Impairment: Ten Years Later. Arch Neurol. 2009 Dec; 66 (12): 1447–1455.

- Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, Xue QL, Harris TB, Purchase-Helzner E, Satterfield S, Ayonayon HN, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM; Health ABC Study Group. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013. Volume 173, 4; pp. 293-299.

- Hosking DE, Anskey KJ. The Economics of Cognitive Impairment: Volunteering and Cognitive Function in the HILDA Survey. Gerontology. 2016;62(5):536-40. doi: 10.1159/000444416.